Takeaways

- Collecting race, ethnicity and language (REL) data supports health equity on the individual and population levels.

- Asking patients to self-report their racial and ethnic identities is the best way to collect accurate data and create an inclusive environment.

- Digital tools can help healthcare organizations collect standardized REL data at scale without burdening staff or patients.

- Creating a better system for collecting REL data can lay a strong foundation for improving other demographic data collection as well.

The first step to achieving health equity is understanding where health inequities currently exist—and healthcare organizations can’t do that without accurate, accessible data about patients’ social identities.

But the need to collect that data quickly and integrate it across electronic systems leads many organizations to miss—or misrepresent—important aspects of patients’ identities. Race, ethnicity and language (REL) data is no exception.

A 2023 study found that 13% of patient races and 6% of patient ethnicities were misreported in a large academic medical center’s electronic health record (EHR). Hispanic and Latino patients were more likely to be misidentified than white or Black patients—and what’s more, all patients who identified as multiracial were misidentified in the organization’s EHR. A review of 43 studies published the same year found that Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native and Pacific Islander patients are misidentified most often across healthcare databases.

We spoke with Kasey McCreery, NP-C, MSHI, Phreesia’s Director of Clinical Documentation, about why collecting accurate REL data drives health equity, how a digital patient intake platform can help collect REL data more accurately and how improving REL data collection can serve as a starting point for transforming patient data collection overall.

Why should healthcare organizations collect patients’ REL data?

McCreery: In the simplest terms, you need to know someone’s race before you can address racial disparities—and you need to know what language someone speaks so you can ask questions and share information they’ll understand fully.

If healthcare organizations know their patients’ REL backgrounds, they can use that information in a few important ways. First, since some health conditions are more common among certain racial and ethnic communities, collecting race and ethnicity information can help providers determine which clinical screenings to offer or diagnostic tests to recommend. Second, healthcare organizations should ideally employ staff who reflect their patient population—and knowing patients’ racial and ethnic identities and the languages they speak is the key first step to hiring representative teams.

Plus, REL data is essential for health disparities research, which uses REL information logged in healthcare databases to draw conclusions about disease prevalence, access to care, treatment, outcomes and other patient experiences. When identities are recorded incorrectly, we’re affecting the accuracy of that research. And since we use research to drive policy and treatment strategies, it’s crucial to make sure it’s accurate.

Underestimating disease burden within a healthcare organization’s or a community’s patient population can even affect how much funding they receive to combat health disparities—and a lack of needed funding can contribute to poorer health outcomes.

“When healthcare organizations use incomplete data, it becomes incredibly difficult to move the needle on health equity.”

In other words, when healthcare organizations use incomplete data, it becomes incredibly difficult to move the needle on health equity.

How do healthcare organizations need to change the way they collect REL data?

McCreery: Many organizations don’t prompt patients to self-report their REL information. Instead, they import REL options from other sources, such as payer organizations, and ask patients to choose one. That’s part of an effort to ensure patient data is standardized, but it falls short when patients can’t find the answer choices that describe them best.

Another example we’ve seen is that administrative staff might assume a patient’s race while creating their record over the phone or at the front desk. But a person’s race or ethnicity can’t necessarily be determined by talking to or looking at them. And if a patient accesses their record and finds out their race was assumed incorrectly, they can feel stereotyped, othered or uncomfortable. As a result, they may be less likely to return for care—at your organization, or any organization—in the future.

Allowing patients to self-report REL information is a critical first step toward ensuring that clinicians have relevant data and that the patient feels understood.

Why is it important for patients to self-report REL data?

McCreery: Recent research makes it clear: Self-reported REL data is the gold standard. Patients are the experts on their own identities, and asking them to describe themselves will result in the most accurate data—and recording incorrect or incomplete data can contribute to inequities rather than help address them.

For example, if staff don’t ask about a patient’s English proficiency, they may assume that the patient is a fluent English speaker. They might schedule the patient to see an English-speaking provider without an interpreter available—and only when the patient arrives for their appointment would the provider discover that the patient has limited English proficiency.

An estimated 8% of people in the U.S. ages five and over had limited English proficiency in 2021, and studies show that unmitigated language barriers lead to miscommunication. That can reduce the quality of care and even pose patient safety issues if a patient can’t fully express their history and symptoms to the provider or understand the provider’s instructions. That’s why it’s so important to ask patients’ preferred language, no matter where you’re based.

How can a digital platform help healthcare organizations collect more accurate REL data?

McCreery: Research shows that digital tools that allow patients to self-record their REL information before, during or after healthcare visits can increase data quality.

That’s why the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) called on organizations last year to improve REL data collection in EHRs—it’s so important that we get this right, and digital tools are a great way to facilitate that.

Because organizations are transitioning away from paper-based processes and adopting more digital-first solutions, we also have a fantastic opportunity to include more representative REL options using point-of-care platforms like Phreesia.

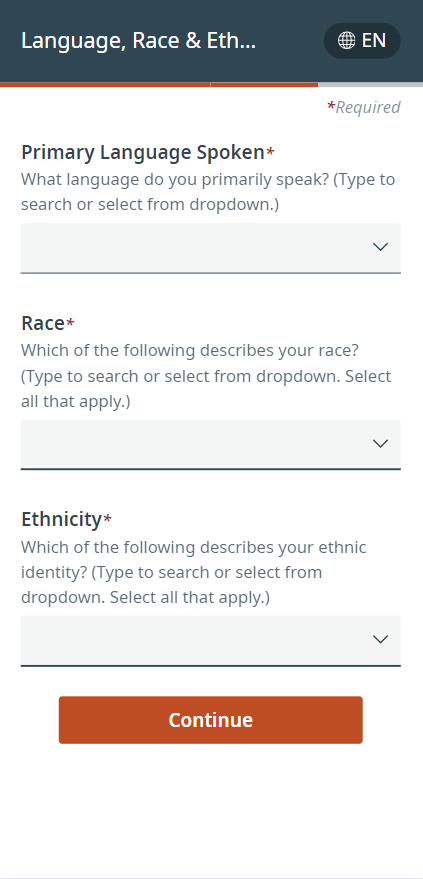

We’re testing a dropdown menu of REL answer choices that’s both inclusive and standardized. Our new menu offers more than 900 answer choices developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that will discretely integrate into EHRs. We’ve also made the functionality easy for patients to use: They simply input their answer choices, and the dropdown will move to the option they’ve indicated so they can select it in seconds.

Plus, we’re asking those REL questions during self-service intake, so a patient can supply this information while checking in on their own time, with their own device. People may feel more comfortable disclosing that information when they can do it privately—and healthcare staff who don’t want to ask potentially sensitive questions in the waiting room may feel more comfortable, too. Not to mention that asking these questions digitally gives us a chance to standardize them, so the questions and answers are the same every time. Standardization helps mitigate implicit bias.

It’s important to remember, though, that we don’t just need to standardize options. We need to present them in a way that encourages patients to be open about their identity.

How can improving the way we collect race and ethnicity data inform the way we collect other patient data?

McCreery: Establishing a better system for collecting REL data can help us collect other demographic data the same way, like information about sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI).

Healthcare leaders have long faced challenges collecting SOGI information. Often, providers don’t ask, or they use question-and-answer combinations that don’t include the full range of identities. And when they do ask, LGBTQIA+ patients often hesitate to disclose their identities due to experiences with homophobia and transphobia, while heterosexual and cisgender patients might not know why it’s important for them to answer those questions as well.

Those challenges have impacted data quality: Just last year, one study found that gender identity was missing for most patients in an urban academic medical center, and 11% of the gender identity data that had been recorded in their EHR was incorrect.

Collecting accurate SOGI data is critical for helping healthcare organizations effectively manage population health and provide identity-affirming care. And when patients can self-describe their gender identities, we can close data gaps and provide the care they need.

Click here to learn more about how Phreesia can help your organization collect more accurate patient-reported data.